Everything posted by Carl Dickson

-

AFCEA WEST Conference and Exhibition

until

Sea Service leaders today must constantly confront profound and rapidly changing threats in a landscape of increasingly complex challenges. Join us at WEST to engage with Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard leaders and industry and academia experts in this extraordinary opportunity to explore the depths of the unique issues they confront. Engage in discussions, network with peers and be a part of devising the needed solutions to enhance operational capabilities that overcome evolving threats. Gain knowledge and forge connections while discovering the latest platforms, cutting-edge technologies and advanced capabilities crucial to supporting maritime operations. Event information and registration -

2025 Healthcare Summit

until

Potomac Officers Club is thrilled to host our year-closing 2025 Healthcare Summit, an essential annual GovCon conference where the most pressing topics in healthcare technology and citizen user experience are discussed. Every year at this event, innovative new ideas are formulated, problems are solved collaboratively amongst speakers and guests alike, and attendees are left with an acute sense of where the federal healthcare industry stands. The foremost thought leaders in government healthcare technology — particularly those supporting warfighter health at places like the Defense Health Agency and Department of Veterans Affairs — will take the stage alongside prominent figures from industry during informative keynote speeches and exciting panel crosstalk. If you’re looking to start new business or strengthen existing partnerships with organizations such as the Department of Health and Human Services or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, this is the event for you. Event information and registration -

2025 Homeland Security Summit

Safeguarding the nation from emerging threats remains a critical priority for the U.S. government in this complex era of defense and security. As global competition grows, new challenges, vulnerabilities and concerns arise. Join the Potomac Officers Club’s 2025 Homeland Security Summit to gain insights into the most pressing threats facing the country and the measures being implemented to counteract them. Topics to be Covered: The latest in U.S. homeland security programs, efforts and strategic initiatives Deployment of new technologies at national ports and border checkpoints Integration of AI and other emerging technologies in homeland security operations Why Attend? Stay informed about key developments in homeland security Learn how the private sector can support government security initiatives Discover networking opportunities and connect in breakout sessions Event information and registration

-

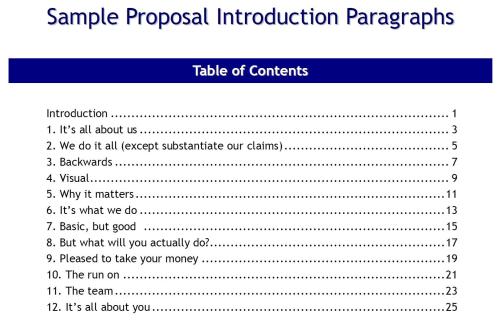

Sample Proposal Introduction Paragraphs

- 11 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

Before we wrote the MustWin Process, we wrote a series of tutorials that included "Sample Proposal Introduction Paragraphs."Free -

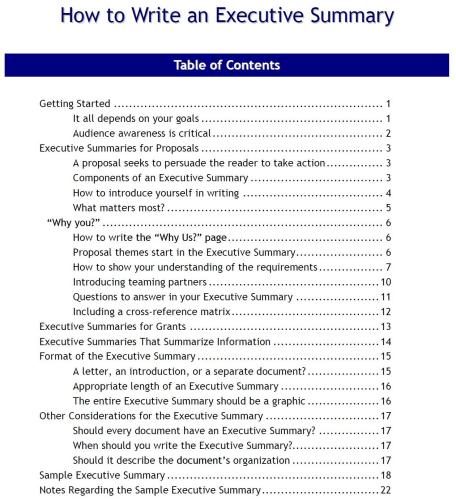

How to Write an Executive Summary

- 8 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

Before we wrote the MustWin Process Workbook, we created a series of tutorials that included "How to Write an Executive Summary."Free -

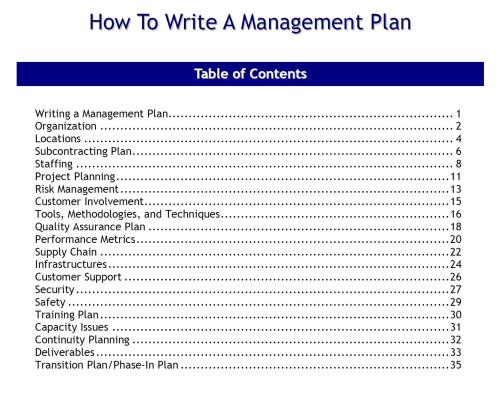

How to Write a Management Plan

- 12 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

Before we wrote the MustWin Process Workbook, we wrote a series of tutorials that included How to Write a Management PlanFree -

AgH20 Capabilities Statement

-

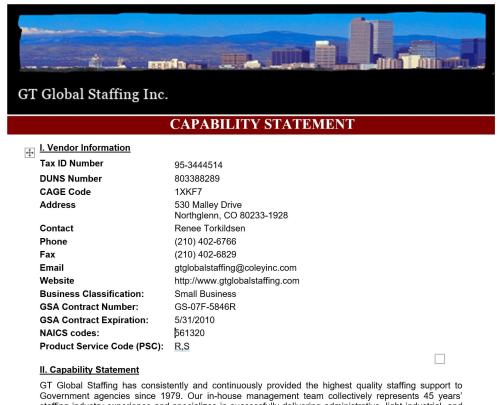

GT Global Capability Statement

-

Sample Architecture Proposals

- 0 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

Sample Proposals for the City of Piedmont Qualifications and Proposal for Civic Center Master PlanFree -

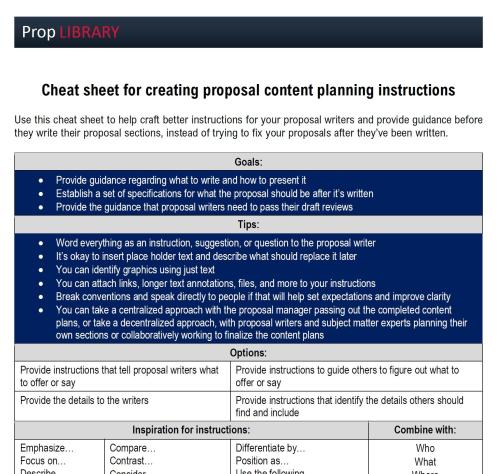

Proposal Content Planning Cheat Sheet

- 18 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

For use during Proposal Content Planning. Provides inspiration for what to include and how to articulate it to guide proposal writers to create the desired proposal.Free -

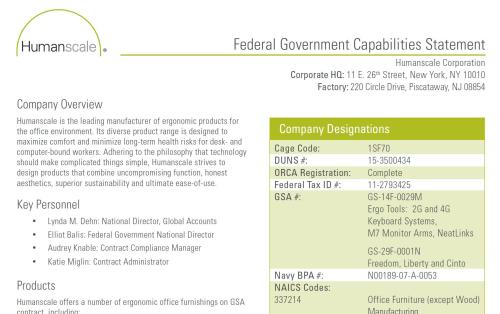

Humanscale Capability Statement

-

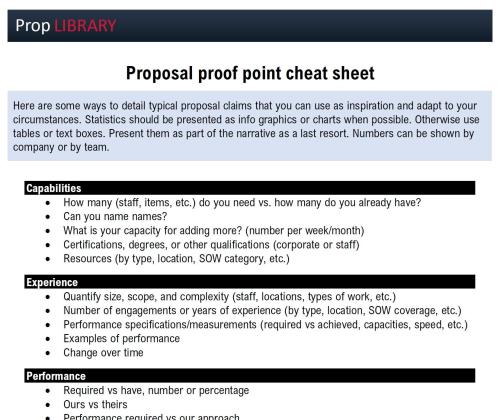

Proposal Proof Point Cheat Sheet

- 12 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

Proof points are vital for winning proposals. But asking people to "insert some proof points" often falls flat. This cheat sheet can help inspire people to supply relevant proof points.Free -

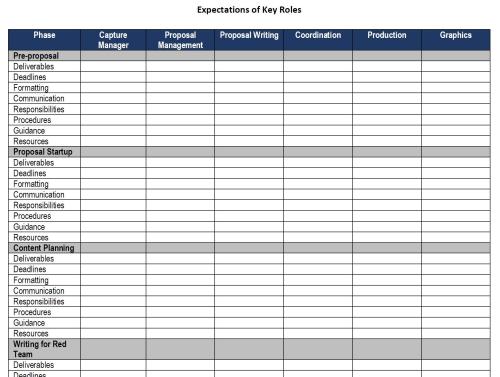

Role Based Expectation Matrix

- 7 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

This matrix enables you to quick document what is expect of each role supporting a proposal through each phase of proposal development. When you view across the roles you can see how the team works together to accomplish each phase.Free -

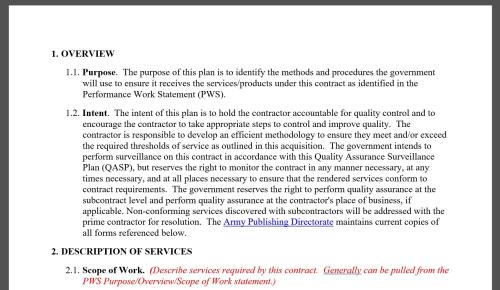

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plans

- 11 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

These templates are to assist contractors in completing their Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan (QASP).Free -

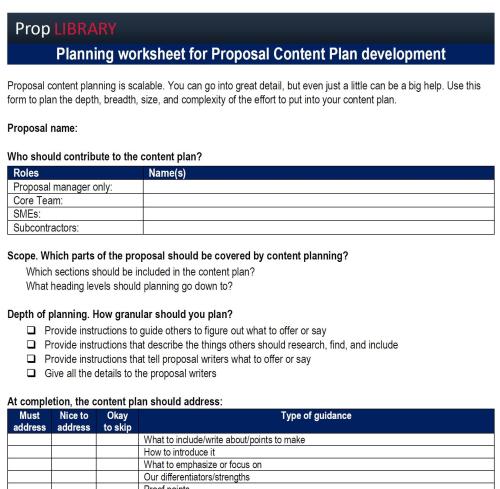

Proposal Content Planning Worksheet

- 7 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

What should you put in your content plans? How should you articulate the things you include? Who will be involved. For individuals, this worksheet provides inspiration. For groups, it helps set expectations.Free -

Course Completion Quiz

-

Best Practice Library

1 of 54 pages of best practice guidance. All categorized so you can find what you need in a given moment.

-

Over 40 critical truths about defining proposal quality (presentation)

- 6 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

A presentation given by Carl Dickson, founder of PropLIBRARY, on the topic of defining your proposal quality criteria.Free -

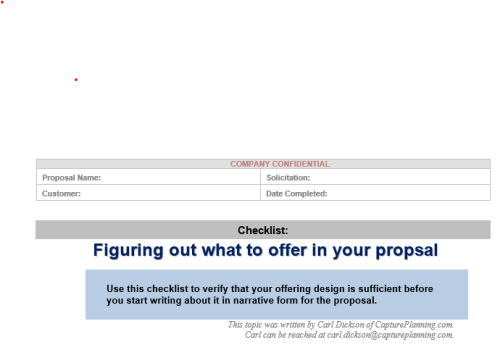

Simple checklist for what to offer in your proposals

- 4 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

A simple checklist to help you figure out what you offer in your proposals.Free -

Over 40 Critical Truths About Defining Proposal Quality

A presentation Carl Dickson, founder of PropLIBRARY gave on the topic of What defines proposal quality and how can you develop quality criteria to assess it.

-

How AI is breaking the way we all do business

If you depend on your website and pay attention to the traffic you get from the search engines, you've probably noticed a decline over the last couple of years. A Pew Research Center report found those who get the AI summaries in their searches visited websites in the search results half as often. And in May, Google started showing these to everyone by default, even if you have not opted in. There have been many other, similar reports. This trend will continue and has incredible implications for the future of everyone who does business. As if that wasn't enough, AIs play by different rules when it comes to intellectual property. And all the benefits of AI could go away if we forced them to play by the rules the way they've been traditionally interpreted. Every business that involves teaching, explaining, and informing based on intellectual property is going to have to transform or wither and die. That includes PropLIBRARY, but we've worked out how to do that. I've spent a lot of time thinking about this, how to not only address the challenges, but to turn them into opportunities for growth. And now I'm ready to talk about not only what we're going to do, but why and how it impacts everybody else. Next week I'll be announcing dates for a series of webinars to discuss it all. The massive changes to the way online business works and the way our society handles intellectual property impact the future in ways that are not obvious. Everyone obsesses over whether AI will change or destroy jobs. What's easy to overlook is that AI is going to completely redefine how we do business. It will change many of the principles our society takes for granted, like those related to intellectual property. It will change how businesses get discovered, how they interact with their customers, what their customers need from businesses, and the exchange between customers and businesses. That pretty much covers everything business. Everything is going to change. On the scale that AI is being implemented as we speak, it will change how the entire economy functions. The days of being able to start a business with a website and grow it over time may vanish. The reason is that search engines as we've known them for more than 20 years no longer exist. Every search engine is moving as fast as they can to become a destination instead of a connector. They are not incentivized to connect their users to the sources they pillaged to create the answers they've given. What are they incentivized to do? Connect people to advertisers. In the future you'll have to pay for every click you get. This will transform how you go about marketing, as well as everything else about websites. But it will also transform everything about teaching, explaining, and informing. And everything else business. So when I say PropLIBRARY is transforming, I mean we're doing paradigm-shifting changes in everything from business model, approach to marketing, product development, and how we plan to interact with customers and business partners. And to make our plan work we have to share exactly what we're going to do. Which, for us is easy, because our business was basically built on over-sharing from the beginning. Stay tuned. Next week we'll announce dates and times for the webinars and how you can submit your questions in advance so we can make sure we address them.

-

Anti-Differentiators: Don't say these things unless you want your proposals to sound ordinary

Saying things that differentiate your offering from your competitors is a well-known best practice. Proposal writers spend a lot of time identifying differentiators and then working them into their proposals. At least they should. What we see in a lot of the proposals we review are things that do the opposite. People write things in their proposals that make them sound ordinary. You can’t be competitive and sound ordinary. We call these statements anti-differentiators. If you can’t write a great proposal built around your differentiators, you should at least try really hard not to base your proposals on anti-differentiators. 5 examples of anti-differentiators Anti-differentiator: “Our company is fully capable of performing the required work on time and within budget.” When you say that you can do the work, you sound ordinary. Everyone who is a potential competitor can do the work. Being able to do the work will not win you the bid. Doing the work in some way that is exceptionally better is what will win you the work. Talk about how your way of doing the work is superior or will deliver superior results instead of simply saying you can do the work. Adding “on time and within budget” to the list is like saying “pick us because we will do a merely acceptable job.” When you claim that you will do the work exceptionally, no one will believe you. So don't say that you are an excellent performer, have a great track record, or will do a great job. Being exceptional must be proven. Ordinary companies claim all kinds of things without proving them. No one ever pays them any attention. No proposal evaluator ever told their boss that they should approve a proposal because the vendor they’d never heard of before said they are the industry leader. A company that proves they have a credible approach to mitigating the risks resulting in more reliable delivery will beat them every time. Anti-differentiator: “Our company meets all of the qualifications required by the RFP.” When you say that you are fully qualified, you sound ordinary. Everyone who is a potential competitor will be qualified. Being qualified will not win you the bid. Being over qualified will not win you the bid. However, being qualified in a way that matters and makes a difference can win you the bid. Focus on why your qualifications will make a difference and prove that it matters. A vendor that brags about “meeting all qualifications required by the RFP” will lose to a company that shows how their qualifications will result in better delivery or that simply offers better qualifications. Every time. Anti-differentiator: “Our company will staff every position required for this project.” When you say that you have the staff or that you’ll just hire the incumbent staff, you sound ordinary. Everyone who is bidding will claim to have the staff or be capable of getting them. And they’ll be just as credible as you are. Don’t just say that your staff or ability to get them is better, somehow. Say what the impact of your better staff or ability to get them will be. And prove it. Anti-differentiator: “We will meet all of the requirements in the Statement of Work (SOW).” If you really want to sound ordinary, say that you’ll fulfill or comply with all of the contract requirements. Because everyone will say that and you’ll have lots of company. You’ll be one of many and just like all the rest. And it’s not even what the customer really wants. It’s merely the minimum of what they must have. What they want is someone who will do better than the contract requirements. Only if you’re going to say that you have to detail how you’ll do that and what the impact will be. Anti-differentiator: “Our company delivers the best value.” When you say that you or your approach provides the best value and leave it at that you sound ordinary. If you prove the value impact of what you offer is greater than the value impact of other offers, then you sound compelling. Only how are you going to do that? The best you can usually hope for is to explain the trade-offs and how the trade-offs you chose will strike the best balance between cost and performance. Skip trying to claim to be the best value. Your claim means nothing. The customer will determine who is offering the best value. And they’ll do it by considering the trade-offs. Information about those trade-offs that help them understand what matters is the kind of thing that customers cite as strengths on their proposal evaluation forms. Don’t be the minimum Anything that involves doing the minimum, meeting the requirements, and being capable, will always be anti-differentiators no matter how affirmatively you state them. Why would the customer choose a vendor who is merely acceptable over someone who is better? Any claims that are unproven, no matter how complimentary or grandiose, will also be an anti-differentiator. They do the opposite of what you intend and make you look like an ordinary, somewhat untrustworthy, vendor deserving of skepticism. Each anti-differentiator that you include in your proposal lowers your competitiveness. Don’t be ordinary because ordinary doesn't win. If you can’t find a real differentiator, at least just prove that you are good at what you do. Proof points can be differentiators.

-

Writing (and winning!) a proposal with the staff you have instead of the staff you need

Not only will you never have enough people to help write and produce a proposal, but many of the ones you do have will be inexperienced. You need to get the most out of what you’ve got to work with. Sometimes this means that instead of best practices and a great proposal, you need to figure out how you're going to be able to submit anything with the staff you have to work with. And hope you can still win. Maybe your proposed price will be low. Basic things you can do to improve your chances Anticipate everything an inexperienced proposal writer is going to mess up and have questions about. Don’t just think about the procedures. They won’t already know what the goals should be and you can’t afford for them to get stuck. They won’t know how to structure their response or what points to make. They won’t know what the expectations are. Keeping them from wandering around in the dark will save a lot of time. Make sure people can fulfill their assignments. It will help tremendously if you have practical guidance you can give those contributing to the proposal effort. It will also help if you take the time to detail your proposal assignments. Most proposal assignments come with failure built into them. If you just pass out an outline, you’re setting yourself up for a bad proposal experience. Detailing your proposal assignments means telling people what they need to succeed with their assignment and not just giving them a heading to fill in. Guide them towards success. Proving training is beneficial, but can increase the time burden that the proposal represents. Classroom training is best for procedures, knowledge transfer, or contextual awareness and pays off best for staff who will do more proposals in the future. But practical proposal training is best embedded into your process and doesn’t have to even look like training. Think of it as guidance that can be implemented in the form of explainers built into forms, cheat sheets, and checklists. A little goes a long way, even if it’s just explainers included with assignments. The further you go beyond an outline and a schedule, the more you will get out of the staff you’ve got to work with. Set the bar low and be careful where you raise it. Decide whether your goal is to submit an ordinary, compliant proposal that no one will be embarrassed by without mentioning that it’s not a competitive strategy, or whether you are going to stretch your thin resources to the breaking point in an attempt to win against better prepared and resourced competitors. You’ll do a better job if you assess your circumstances and make an intentional choice between those two instead of leaving it unstated or claiming to do both. Going all heroic without the right resources tends to result in a last minute train wreck of a proposal full of defects that no one will want to admit to. Going beyond the basics to really get more out of people If you only task your proposal writers with writing, you are in for a bad proposal experience when insufficient and inexperienced staff try to figure out what to write and how to present it on their own. There is a lot more to winning a proposal than showing up and putting enough words on paper to fill the page limit. The more you do to goals and expectations instead of procedures. Build for the future In this moment on this pursuit, the staff you’ve got to work with is limited and the best you may be able to do is accelerate the time from thinking to writing and eliminate rework. But over time and on future pursuits, you can improve those staff and possibly find new ones. Building people’s awareness about how to streamline the writing through planning and improving their understanding of proposal quality criteria will benefit future proposals. How much to invest in proposal staffing is an ROI consideration. If you want The Powers That Be to better resource your proposals, you need to show the impact that will have on revenue, and that the return is orders of magnitude more than it costs. The converse is also true. Understaffing proposals will reduce revenue by far more than it saves. Maximizing ROI depends on improving your win rate. Regardless of whether your proposals are fully staffed, understaffed, or most likely somewhere in between, improving the effectiveness of the staff you’ve got to work with will always be part of improving your win rate.

-

I was today years old when I learned what proposal management should really focus on

Proposal management is not just about implementing the proposal process. Procedural oversight is an archaic view of the primary role of management. Proposal management should be about accomplishing the goal of submitting a winning proposal. Having a process does support that goal, but a more important part is looking beyond the process to what is required for people to be successful and guiding them to achieve it. Proposal management is more about things like training and problem solving than it is about procedural oversight. Proposal training itself is about a lot more than just procedural training. By default we think of training as learning what to do. We always seem to want to start with Step 1. But the reality is that proposals aren’t really a developed in a series of sequential steps. Proposal training needs to cover expectation management, issue resolution, and seeing things from the customer’s perspective as much as it should cover the proposal lifecycle. When it comes to proposals, “what to do” is fifth in line even though it’s often the first thing people ask for. Ahead of it should be: What are the goals? Developing great proposals is best done through a series of accomplishing goals instead of following steps. Understanding the goal people are trying to accomplish is more important than which procedures they follow to accomplish it. This is because it is completely possible to follow procedures and not achieve any of the goals. What to expect from each other. You can’t fulfill stakeholder expectations if you don’t know what they are. This is the basis for how people work together and not the “steps” in the process. How to prepare. Being able to get the right information in the right format so that you can turn it into a plan before you start writing will do more to ensure success than any skills you might have at writing. The most highly skilled proposal writers in the world will lose to highly skilled proposal writers who are better prepared. Every time. How to validate that you did it correctly. Most proposal writing is… ordinary. Ordinary is not competitive. Most proposal writers can’t define proposal quality. Think the two might be connected? Learning how to define proposal quality criteria, use them as guidance for writing, use them for self-assessment, and use them to validate that what was written is what it should be will do more to ensure success than clever wordsmithing. What to do to accomplish the goal. What can be done? What options are there? What must be done? What must be done in a particular way? Proposal procedures can be accelerators that prevent people from having to figure out what to do to accomplish the goals. Presented this way, people more readily accept steps and procedures. But what is important is achieving the goals and not procedural compliance. The doing part of proposals becomes straightforward when you first understand the four things that come before that doing. And to the extent that you have a proposal process, it should do these things first, before tasking people with assignments. The management of proposals is practically built in when you have goals, expectations, preparation, and validation in place before the doing. The challenge for proposal contributors is learning what goals to accomplish, what is expected, how to prepare before writing, and how to validate proposal quality. This should be the focus of proposal management and proposal training. Give me someone who has learned these things and we can win. Give me someone who has not learned these things and we’ll be able to submit… something. The good news is you don’t have to deliver hours of training for each of these before you start. You just need to communicate things and give people handy checklists and reminders: Do you even tell people the goal for each activity? Do you put it in writing? We recommend using a goal-driven process instead of a step-driven one. What do you do to set expectations? Do you define the expectations for each activity? Is it all talk? Or is it in writing? Do you provide it as a handout? Learn how to communicate expectations in writing during every activity, event, or phase. An assignment without written expectations is just telling someone to do something and not how to do it. An assignment with expectations helps people work together. How do you help people prepare? Do you tell people how to prepare before you need them to do something? Do you give them time to prepare after you’ve told them how? Or do you wait until they fail to give you what you need? Every task on a proposal requires input. Planning How do you validate that proposal assignments were done correctly? Do you enable people to self-assess their work? Do you give them the same criteria that the proposal reviewers will use? Or do you set them up to be surprised at the review? How do people bring you completed assignments with a high likelihood of them being well done without it just being based on opinion and hope? We recommend enabling proposal quality validation by having written quality criteria. They can even take the form of checklists. Always give writers and reviewers the same criteria. Proposal management after the fact without these things is just complaining and attempting to fix things that shouldn’t have shown up broken. Proposal management with these things is competitive. It’s managing to win instead of managing to submit.

-

New Training: Win more proposals by improving how you define and communicate expectations

Most proposal issues have at their root the fact that we have to work with other people, with different needs, agendas, and expectations. We come together for a proposal and bring our expectations. When those expectations go unfulfilled or conflict, problems result. And those problems ultimately hurt your win rate. This course provides a structured approach to define and communicate proposal expectations so that we can work more smoothly together and maximize our win rate. The target audience for this course: This course is for companies with RFP-based proposals large enough to require a team of people to contribute. It is equally relevant to large government contractors as it is to small businesses trying to make the leap from one person who's done all of their proposals to an environment with multiple contributors. A little history to put things into context… In 2004, Carl Dickson of CapturePlanning.com launched the MustWin Process as a fully documented proposal process with innovations to improve win rates. In 2017, we began migrating the MustWin Process from a milestone-based process to a goal-based process, in which achieving the goals were more important than the steps used to achieve them. This opened up tremendous flexibility. In 2021, we began developing a new model for proposal development, based on defining expectations instead of steps. When combined with the goal-driven MustWin Process, it achieves full awareness of what needs to be done, what is required to do them, when they need to be done by, and how to assess whether they were done properly. In practice on real world proposals we are finding this to be transformative. People don’t need to follow a flow chart that breaks with the first curveball thrown by an RFP. Proposal contributors and stakeholders can all know what’s expected of them for every activity without even asking. When there are issues, the expectations are clear so that the team can focus on resolving the issue in a way that puts them back on track. People are less likely to ignore a set of written expectations that will come up later if they do. People tend to appreciate having the expectations spelled out at the beginning. We’re ready to teach our model to you, along with how to apply it across the life of the proposal. We’ll focus on the key roles contributors and stakeholders play so that everyone will understand what expectations they need to fulfill during a proposal. In this new training course, you will learn to use our Expectation Model to: Enhance an existing proposal process. You'll learn how to bring more clarity to the people participating. As a step toward formalizing how you do proposals. If you don't have an established process or it isn't well documented, in this course you'll learn how to build a foundation for better proposals. To be honest, you can get by without a Proposal Process if people understand the expectations for working together. And once they do, implementing a process later becomes an easier, incremental step. The real issue isn’t whether, how much, or what type of proposal process to have. The real issue is how to improve your win rate and how to get there from here. This course will give you what you need to improve your win rate on the people level instead of the flow chart level. But the two can work together. Eliminate friction during proposals. More proposal friction is caused by unfulfilled or conflicting expectations than any other cause. Except maybe for RFP amendments ;-) Address expectations with a 360-degree perspective. All proposal stakeholders have expectations that flow in every possible direction. And they all matter. Improve efficiency. People should know the expectations without having to ask. “Work late until it’s done” is an example of a poorly communicated and flawed expectation for a very real need. That need can be better addressed with better expectation management. Handoffs between people go much more smoothly when expectations are clear. Smooth handoffs mean effort spent on improvement instead of rework. Increase your company’s competitiveness. When everything else is the same, the proposal team that works together the best has a competitive advantage. If you are in a line of business where differentiators are hard to find, this becomes even more important. Introduce beneficial change over time. Expectations change. And when they do, you need an effective way to communicate the changes. If you have a model for defining and communicating expectations, you can use it to introduce change. Got a recurring problem? Change the expectations to prevent it. Got a lesson learned? Change the expectations to address it. Got an RFP mandated curveball that no one would expect? Now you’ll have a way to change and communicate the expectations for each stakeholder group throughout the process. Overcome problems with process buy-in and acceptance. Resistance happens when people are asked for things that are too far out of line with their expectations. When you improve how you communicate expectations you reduce resistance and increase acceptance. Or you surface the issue. The real problem is how do you resolve the expectation conflict? Having a structured way to declare expectations gives you something you can change if needed to gain acceptance. Expectations flow in both directions. You want to address your stakeholders' expectations as well as your own. This course will put you in position to be able to do that. What does this course consist of? Two 1.5-hour zoom sessions per week, for four weeks Examples you can tailor Homework assignments to research and articulate expectations Conversion of expectation lists into checklists and assignments The first cohort for this course will be on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 11am, starting on February 7th, 2023. Pricing You have two options, single participant and dedicated group: Single participants are $1,595 with a $600 discount if you are already a PropLIBRARY Annual Subscriber or become one first. Dedicated groups: $5000 with only your company participating, up to 30 attendees, and 3 free annual subscriptions ($1500 when purchased through our website) or renewals to PropLIBRARY Invite your key stakeholders to participate in defining expectations Use company specific role definitions and milestone terminology By the end of the course you will complete a ready-to-implement expectation matrix that will transform your process Schedule at our mutual convenience Inflation fighting tip: You probably waste more than this in B&P spending on every single proposal you do, due to issues that directly result from problems with expectation conflicts... A day of schedule slippage here. An extra day of review recovery that should not have been necessary there. A tenth of a percent point decrease in win rate due to having to lower the bar instead of raising it… Multiply by the number of people impacted and soon you're talking real money that this course can help you stop wasting. Instead of fighting inflation by reducing the headcount on proposals (which we both know will lower your win rate), try reducing the number of wasted hours instead. How do I enroll? Click this button and let us know whether you would like to enroll as one or more single participants or as a dedicated group. Based on the option you select, we’ll check your PropLIBRARY membership status and send you an invoice for online payment, with payment by check as an option. Along the way, feel free to ask any questions you may have. Register, ask a question or get more information We strongly encourage you to make sure you are a paid subscriber to PropLIBRARY first so that you can take advantage of the discount. You can become a subscriber to PropLIBRARY here.