Everything posted by Carl Dickson

-

9 ways to change attitudes and improve corporate culture

Most corporate cultures are a mixed bag. Other than aspirations, no real effort is put into it. As a result, it is defined as much by the personalities of key staff as it is by intent. Without nurturing, a corporate culture will grow like a weed instead of being designed. If you are in charge, the odds are that your corporate culture is not what you think it is. The reality is different from your aspirations. The reality is how people are behaving when you are not in the room. How your proposals go tells you a lot about your real corporate culture. The decisions they make, how they engage, how they cooperate, and how they disagree all surface. Their real priorities, goals, and agendas also surface as they deal with conflicting priorities. You can see whether people reflect or ignore the stated corporate values. The result is how well they perform and that directly impacts the company's ability to win new business. Your corporate culture is as important to your company’s ability to grow as the steps in your business and proposal development processes. So what do you do about it?How do you go about changing a culture? It’s not just about speeches. It’s not just about how people treat each other. It’s about changing behaviors. But behaviors don’t change just because the boss says they should. It helps to model behaviors. People tend to emulate their leaders. It also helps to synchronize how people do things with the results you want to achieve. Unfortunately, when the leaders behave in a negative way, that tends to get emulated as well. When the leaders describe the culture in a certain way but model different behaviors, the culture will not actually become what they describe. Here are nine examples of things you can do to change the culture in your organization to one that encourages behaviors that support winning: Require all levels to focus on ROI. The economics of resource allocation and priority setting should be based on ROI and not cost control. That should become part of the culture, encouraging people to track ROI and make decisions accordingly. Focusing on ROI shifts the debate from what is the least expensive way to win contracts to what is the most effective way to win contracts. This is where I like to start with companies, since understanding their pipeline and how to calculate the ROI of business development and proposal efforts drives so many other decisions. Focusing on ROI helps companies pay more attention to their win rate. Require achieving top performance measures. For Federal contractors, having a top past performance score is critical for being competitive. Instead of making "the highest levels of customer satisfaction" a "value," I recommend making it a mandate. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the top score, the company's expectation should be that all projects will score a 5. Scoring below a 5 shows a disconnect between the customer and the company, and should be corrected immediately. You can't be a winning, high-growth company if you are disconnected from your customers. You need your project managers to advocate for the customer and help the company understand the customer’s expectations. Make evidence-based decisions. Bid/no bid decisions should be evidence based, with the burden of proof on why leads are worth bidding based on ROI. Having the evidence means tracking metrics and measurements to provide the data required. Arguments should be over what the data means and how to get more of it, instead of about opinions. A company focused on evidence of performance and quantifying ROI will make better decisions, win more business, and be more profitable. Define accountability properly. If your approach to accountability is based on authority or a chain of command, it will reduce the quality of your proposals. Great proposals are not written in fear. That's how you get merely compliant proposals. Maybe. Go back to the root of the word and think about the practice of accounting. Accountability should be based on information accuracy and feedback loops. Accountability should not ensure that every step is precisely followed. It should ensure that goals are accomplished by informing those responsible. Accountability should enable people to do the right things and inform them when they have deviated. You don't want people spending so much time accounting for their responsibilities that they don't have enough time to excel at them. Also, it's good to remember that most innovations come from deviations. When people avoid innovation because they are too busy establishing accountability or are afraid that being accountable means being subject to being punished, you get well-executed proposals that are not competitive. You can flip the script on this by focusing on accomplishing goals and being tolerant of how they are achieved. Make accountability about accounting for the information people need and what to do with it so they can better achieve their goals. Validate quality. Quality should be validated and not simply claimed. If your company values "the highest levels of quality" no one will pay it any attention. But if it values the validation of quality, then action is required. And validating quality will start by defining it. Making this part of your culture means that everything people do should be checked to make sure it got done in the correct way. It means every assignment should be defined and have a means to verify that it was properly completed. Most proposal assignments are defined, but no one has anything more than a feeling about whether they were successfully completed. Give them the means to validate successful completion. When this is part of your culture, it becomes simply the way people work. And it is a much better way of working than trying to satisfy whims. Implementing this requires completely changing how most companies conduct their proposal reviews. Cherish customer insight. The best competitive advantage is an information advantage. Gaining an information advantage requires customer insight. If growth is your top priority, then every single customer interaction by every single person who has customer contact should be part of a coordinated effort to gain customer insight. This should not simply be a standard operating procedure, it should be part of your culture. Gaining customer insight should be part of what you do, at all levels and in all departments. This is a key step toward ensuring that all of your proposals reflect customer insight. It takes more than a salesperson or a capture manager. Throw the whole organization behind it to create a culture of winning. Most operations staff can't explain what customer insight is, let alone how to get it. If your organization is like that, try teaching them about gaining customer insight to get better results. Value perspective. Your entire proposal should be written from the customer's perspective and not your own. You need to train your organization to see things through your customer's eyes. When you achieve that, your staff will also be able to see things through each other's eyes as well, and better understand how to work together. When winning is determined by someone else, perspective becomes a key ingredient. Perspective avoids the stovepipe mentality, departmental walls, and excessive bureaucracy. Perspective facilitates teamwork and collaboration. Perspective across the organization is needed for being a winning organization. Advocate creative destruction. You can claim to value "innovation" all day long, but how do you actually make innovation happen within a company? When you advocate creative destruction, you encourage looking for ways to obsolete the status quo. You might prefer to call it reengineering. Or continuous improvement. But the key to it is continuously obsoleting the status quo. This should inform staff looking for what offerings to develop or solutions to propose. It also directly contradicts people who have a fear of doing something new that might cannibalize an existing business line. It sets the stage for disruptive marketing. It's about competing by changing the rules, instead of following the pack and trying to work your way to the front. Institutionalize clarity of expectations. Failure to manage expectations leads to friction. Sometimes lots of friction. Win rate killing friction. Assignments that shouldn't have been accepted go unfulfilled. People meet deadlines with substandard work. People are asked to complete assignments without being told how or by what definition of quality until they hand in their completed assignment and find out it's wrong. Achieving clarity of expectations works in both directions. Not only must assignments be clearly given, they must also be accepted. Or not. Or discussed. Anything but passive acceptance leading to predictable failure. Availability, capability, and progress reporting also depend on clarity of expectations in both directions. All proposal expectations should be discussed, reviewed, verified, and confirmed by all parties. When expectations flow in both directions we get collaboration instead of rework and substandard submissions. The difference between tasking and cultureMandating reports to track performance is not the same thing as building a culture based on evidence-based decisions. When you mandate reports, people will do what is required. When you have an evidence-based culture, people will think differently. Complaining about quality is different from having a culture that prevents quality issues by validating everything habitually. Making understanding the customer the salesperson’s job puts all your eggs in one basket and doesn’t ensure that insight makes it into the document that closes the sale. Imagine how your work environment changes when leadership models ROI-based thinking based on evidence-based decisions, translated into a clarity of expectations during collaboration, and implemented with quality validation driven by customer insight that leads to an awareness of the customer's perspective, which is then translated into solutions that go beyond the status quo and result in top past performance scores. Let that run-on sentence seep into your culture, not as a mandate, but as simply the way you do all the things. When it becomes habit and becomes part of the way things are done in your company, it has become your culture. WhyBecause you want people to do these things without being told to. Because your corporate culture is as important to increasing your win rate as the steps in your process. Because win rate is critical for growth. And growth is the source of all opportunity.

-

PSC Cyber Webinar on CMMC Compliance in Defense Contracts

until

DESCRIPTION Please join PSC’s Cybersecurity Working Group for the first in a series of virtual webinars focused on helping companies across the defense industrial base understand and navigate the complexities of the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) compliance as a prerequisite for bidding on Department of War (DoW) contracts in 2026 and beyond. Presented by PSC’s Cybersecurity Working Group. PANEL SPEAKERS: • John Nolan, VP, Compliance, ISI Defense • Eric Crusius, Partner, Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP • Steve Harris, VP, Defense & Intelligence, PSC • Christian Larsen, Director, Emerging Technologies, PSC (moderator) This inaugural webinar will cover: 1. An overview of CMMC rulemaking and what it means for companies pursuing DoW contracts 2. Navigating CMMC compliance requirements within DoW contracts 3. False Claims Act risks and enforcement considerations 4. The 2026 outlook and emerging contracting opportunities PSC encourages companies of all sizes and business classifications to register for this timely discussion. If you have questions or would like to suggest CMMC or other cybersecurity topics for future webinars, please contact Christian Larsen, Director of Emerging Technologies, at larsen@pscouncil.org. Note: Future webinars will focus on practical CMMC readiness considerations, including compliance checklists, flow down implications for suppliers, and strategies for positioning your business for DoW contracts with CMMC requirements. More information -

Contracting Working Group Meeting

until

The Contracting Working Group meets monthly to discuss the latest developments in acquisition policy and looks for opportunities to improve the federal procurement system that would benefit both government and industry. Commonsense policies and consistently applied procedures for how and when the government acquires services can greatly enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the federal acquisition system. In many areas, improvements to government business and buying policy—whether through statute, regulations, or agency guidance—will lead to positive outcomes that far exceed the magnitude of the changes themselves. More information -

How to optimize your Executive Summary to get the highest score

Thanks! Putting the customer first instead of yourself is a good thing and helps make the proposal about them instead of being about yourself. This may not be what you had in mind, but the words you used made me remember something that I've seen a lot of companies do. I should have added "Ask yourself whether you matter to the customer" to the article. Based on the evaluation criteria in the RFP and what the customer is procuring, sometimes qualifications matter a lot. And sometimes they take a back seat to performance metrics. Sometimes experience is the most important thing and sometimes is just a checkbox. A company's mission, vision, commitment, pride, or how happy they are to submit their proposal almost never earn a single evaluation point. Instead, they waste space and force the customer to read material that is not relevant to what they need to do.

-

CES 2026

until

CES is a trade-only event for individuals 18 years of age or older and affiliated with the consumer technology industry. The world’s most powerful tech event is your place to experience the innovations transforming how we live. This is where global brands get business done, meet new partners and where the industry's sharpest minds take the stage to unveil their latest releases and boldest breakthroughs. Get a real feel for the latest sol... January 6-9, 2026 Organizer: Consumer Technology Association (CSA) Location: Las Vegas, NV -

Fed Expo 2026

The Fed Expo event is back at the Holiday Inn Capitol-National Mall. Now that federal government workers are back in their offices, this event provides a great opportunity to engage with multiple federal agencies. The location of the event is central to several government agencies, such as FEMA, HHS, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Education. Additional agencies that are located within a 2-block radius that will receive promotional materials include DHS, GSA, CDC, and The Smithsonian. If your company is working on advancements in any of these technology fields, your company is encouraged to exhibit: In addition to currently posted acquisition priorities for each agency, the following product areas are in high demand across nearly all agency procurement forecasts: Video Teleconferencing Modernization Advanced VOIP Direct Clout Connect Zero Trust Networking WiFi6 Unified Device Visibility and Control SOC Modernization Cybersecurity auditing Cloud Migration Configuration Management Infrastructure Automation Edge Computing LEO Sats Privacy Protection ID Management Cloud Security Collaboration Tools Additional Resources: FEMA IT Strategic Plan: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_ocio-overview-it-strategic-direction.pdf HHS IT Strategic Plan: https://www.hhs.gov/about/strategic-plan/2022-2026/index.html Department of Energy IT Strategic Plan: https://www.energy.gov/lm/strategic-plans Department of Education IT Strategic Plan: https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/about/reports/strat/plan2022-26/strategic-plan.pdf Department of Homeland Security Strategic Plan: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2023-05/DHS%20OCIO%20Strategic%20Plan_2019%20to%202023.pdf GSA OneGov Strategy: https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/newsroom/news-releases/gsa-unveils-onegov-strategy-04292025

-

Fort Benning Human Performance Symposium

The Human Performance Symposium will take place 21-22 January in McGinnis-Wickam Hall (MCoE HQ, Building 4) at Fort Benning, GA. This event will focus on the Holistic Health and Fitness (H2F) program that has revolutionized how the Army views individual Soldier health, fitness and readiness. The event will feature presentations from Army leaders and H2F domain subject matter experts from the health and fitness community, industry and academia and breakout sessions on each of the H2F readiness domains: physical, mental, nutritional, spiritual and sleep readiness. The industry exhibition, held on the first day of the event (January 21st), will feature products and services that support the health and readiness of the everyday soldier. Event information page

-

CMS Industry Forum

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Industry Day Forum will be hosted by Office of Acquisition and Grants Management (OAGM) in-person at CMS Baltimore. The format will include briefings from various CMS components, executive leaders, and industry leaders. From the CMS website: Office of Acquisition and Grants Management (OAGM) Functional Statement: Serves as the Agency's Head of the Contracting Activity. Plans, organizes, coordinates and manages the activities required to maintain an agency-wide acquisition program. Serves as the Agency's Chief Grants Management Official, with responsibility for all CMS discretionary grants. Ensures the effective management of the Agency's acquisition and grant resources. Serves as the lead for developing and overseeing the Agency's acquisition planning efforts. Develops policy and procedures for use by acquisition staff and internal CMS staff necessary to maintain efficient and effective acquisition and grant programs. Advises and assists the Administrator, senior staff, and Agency components on acquisition and grant related issues. Plans, develops, and interprets comprehensive policies, procedures, regulations, and directives for CMS acquisition functions. Represents CMS at departmental acquisition and grant forums and functions, such as the Executive Council on Acquisition and the Executive Council for Grants Administration Policy. Serves as the CMS contact point with HHS and other Federal agencies relative to grant and cooperative agreement policy matters. Coordinates and/or conducts training for contracts and grant personnel, as well as project officers in CMS components. Develops agency-specific procurement guidelines for the utilization of small and disadvantaged business concerns in achieving an equitable percentage of CMS' contracting requirements. Provides cost/price analyses and evaluations required for the review, negotiation, award, administration, and closeout of grants and contracts. Provides support for field audit capability during the pre-award and closeout phases of contract and grant activities. Develops and maintains the OAGM automated procurement management system. Manages procurement information activities (i.e., collecting, reporting, and analyzing procurement data). Event information page

-

The AFCEA Atlanta National Security Conference

until

The AFCEA Atlanta Chapter invites you to register for the National Security Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Conference, taking place March 11-12, 2026, in Atlanta, Georgia. Registration is free for U.S. Government and U.S. Military personnel! Join government, military, and industry experts for two days of networking, keynote presentations, and hands-on cyber exercises. Sessions will cover national security topics, cybersecurity, critical infrastructure, quantum resiliency, zero trust, artificial intelligence, drone security, enforcement, compliance, federal, state, and local programs, agencies, digital transformation, modernization, efficiency, and more! The industry exposition will take place in immediate proximity to the agenda sessions. The February 2025 conference hosted more than 50 industry exhibits from companies such as CACI, BigID, Belkin, Bastille, Bank of America, Commvault, CompTIA, Diligent, HDIAC, Ericsson, Everfox, Fognigma, GillmanBagley, HCL Software, Hitachi, NETSCOUT, Opentext, Paloalto Networks, Penn State University, Recorded Future, Saviynt, Redseal, Servicenow, SCSI Testing, in2ai, Tenable, Trellix, CDC, WGU, ZeroFox, Vectra, GSA, DHS, and more. This conference provides an Atlanta-based opportunity to gain insights, connect with industry leaders, and explore the latest developments in National security, cybersecurity and critical infrastructure security. Network with peers at the reception, observe live cyber exercises and participate in sessions and keynotes through the conference. For more details and to register, please visit the event website. -

New Member Introduction – Happy to Join the Community

Welcome. As an Insider you'll be able to network with other Insiders and discuss business and proposal development with other professionals. This is in addition to making use of our expert content and online training. We're all here to improve our win rates. Here is the link for becoming a PropLIBRARY Insider: https://proplibrary.com/subscriptions/ I look forward to talking to you there.

-

What does it really mean to be RFP compliant in a proposal?

That is a bit too specific. But I also I suspect that it will vary by region and possibly other factors. Some things to consider: How low is your overhead compared to your competition? Do you have any advantages like proximity that could impact delivery costs? Are you supplier costs the same or lower than your competition? This is a bit off the topic of the article where it's posted. Normally I'd move it to our B2G forum, but since you're not a subscriber yet I'll probably move it to the Pre-Purchase Q&A forum and we can discuss it further there. As a subscriber you can get notified of replies.

-

What does it really mean to be RFP compliant in a proposal?

I love that you described being enamored with strict compliance as a buzz-kill because 100% compliance is simply not possible when the RFP is subject to interpretation. And they all are. Some a lot more, some a little less. The problem with people who obsess over compliance and demand it, is that they are asking for the wrong thing. it's like asking for risk to be eliminated when it can only be mitigated. And then failing to manage the risk. Aiming for 100% compliance means that what you write will overemphasize some things that don't matter to the customer. And in a page limited proposal, this means you will be underemphasizing some things that do. Understanding what matters to the customer is so valuable. But even when you aren't sure, you still need to try to prioritize by what you think might or should matter to them. An absolute view of compliance gets in the way of doing that. Compliance is near the top of what matters to the customer, but what they consider compliant is not absolute. And it is often, and dare I say usually, not the most important thing to them. Everyone who makes the competitive range will be sufficiently compliant. One you get there, compliance no longer matters. It's human nature to be afraid of small risks with big consequences. You have to overcome that to write proposals with an emphasize on winning instead of not getting blamed.

-

How do you demonstrate thought leadership in a proposal?

Thanks. I can't remember whether i used the words or not, but I agree with them. Customers are unintentionally tricky. They ask you to describe things when what they really want, and even more importantly what they reward, are explanations.

-

8 things great proposal writers do differently

You make a good point. Proposal writing is more like cooking than art. There's preparation involved. You have to gather and assemble your ingredients. You can't just make up greatness. The thing about roles is that you need to understand who they fit together. On a one-person proposal, all the roles still have to be fulfilled. You just have to do them all yourself. On a bigger proposal, there will be others, but they still fit together in expected ways.

-

The new PropLIBRARY has been launched and has a lot of new toys to play with

What can you expect?You can expect more. We’ve added a community on top of the massive amount of content we’ve created. We’re also opening up our platform to other authors. So over time you’ll see a lot more online training and events posted. Service providers, consultants, and trainers will be available to you. All of it is delivered in an updated, easier to use interface. This was a massive refresh. The online training has also been updated, and the downloads are more accessible. An all-new events calendar has been added. PropLIBRARY is now far more engaging, with discussion and networking features wrapped around our content. You can discuss our articles or start discussions of your own. You’ll want to become a member. Here’s why:How do you beat AI-written proposals? Bring insight and intelligence that isn't available online. We’re bringing nearly all of our content inside the paywall so that AI bots can’t steal it and to give you a competitive advantage. Access to our exclusive content is not going to be available via web searching or AI. Becoming a PropLIBRARY Insider will help you create AI-written proposals that will beat all the other AI-written proposals. To help you make this transition, we’ve created a low-cost subscription option that’s 80% lower than anything we’ve ever offered before. It gets you inside the paywall so we can engage further. We even have a way that you can get your subscription free of charge by making referrals... What's the first thing you should try once you’re inside?I couldn’t narrow it down to just one. Meet other professionals, share insights, and learn from each other. Network. Find resources. Get hands-on help with your pursuits. Try commenting on your favorite articles. Or asking a question about one. If you have a topic or question of your own, try starting a discussion. When you see an article of interest, try clicking on one of the tags below the description. They immediately filter our content down to the topic of the tag you clicked on. This is great for focus and relevance. The second thing you should try after posting is all the new Activity Stream options you have. They make following conversations and staying in touch with other people much easier. Remember, if you don’t send messages, you won’t receive any. Here’s the easy way to post: Ask questions Make observations Tell a story Share an insight Reply to someone else’s post If you are a consultant, let’s talk…You can now publish on our platform and get in front of our huge audience. You can post your events. You can create and sell online training. You can tap into our audience collective. Reach out to us for more details. How we’re celebratingWe’re going to throw a party. It’s a virtual thing. It’s going to be a posting party. We’re going to get to know each other and interact as people while posting questions and comments about mostly professional things. Let’s have fun with this! We might make it a regular thing. Here’s the format: We’ll be hosting it on Zoom webinars, but it’s not going to be a presentation. It’s going to be casual. Bring cocktails, snacks, or whatever makes you comfortable. We’ll have our cameras off, so we can be real. We’re going to have a series of topics that we’ll post on. Everyone will be expected to post something. And then we’ll reply to each other’s posts. All while talking and keyboard chatting in a casual way with a low-key party vibe, about anything besides work. The topics will be: Networking so people think we’re being professional. We’ll post about what kinds of people you’d like to network with and where we work. We’ll get to know each other and meet new people without it having to be a big deal. What kind of stupid things have you caught AIs doing? This will be a fun take on a hot topic. Comparing and contrasting B2G, B2B, and International proposals so we can all get out of our box and risk learning from someone who does things completely differently. Service providers, consultants, trainers, products, tools, and associations. They are resources. They also happen to be people too. The party will be in the evening (7:30pm GMT-5) in North America, and the rest of the world will probably be sleeping. We’re thinking about scheduling something on another date and a better time for people on other continents so you don’t miss out on the fun. Register for the Posting Party! If you can't make it, you can still subscribe, become an insider, and post when you are available.

-

I'm an expert consultant. Is PropLIBRARY worth it for me?

Give value to get value. Demonstrate expertise instead of claiming it. I share overshare insights and approaches. I don't claim to be "one of the world's top experts in proposals". I write about proposals and let the reader decide. After I've given value, when it's time to sell I offer. I don't use consumer marketing practices on business customers. I don't advertise to them, I let them know where they can get more of what I've shown. I invite them. Everyone who is a PropLIBRARY Insider chose to accept the invitation so that they could be part of conversations like this.

-

The new PropLIBRARY is live!

Welcome to the newly upgraded PropLIBRARY. We are still testing, cleaning up some loose ends, and reformatting a few things, especially in the Online Training area. We've got about a week's worth of work to do, but it's on stuff that hopefully you won't even notice. If you are a guest, you will be able to see what content is here, but you won't be able to open things. If you are a subscriber, you should find the content is much easier to navigate, filter, and search. But most importantly, every article can now be discussed. And we have a separate area for discussions and networking. If you want to help out, then before you leave please post a comment in a forum or on an article. You get extra credit if you're the first to post! Thanks!

-

I'm an expert consultant. Is PropLIBRARY worth it for me?

For consultants, PropLIBRARY is mostly about: Content marketing to potential customers Ongoing career and personal development, because you can never be expert enough and need to keep up with the times If you are an expert, then you already understand the importance of ongoing development. So let's talk about marketing to potential customers. Someday we might allow advertising, but that's not what we're really about. What we're about is engagement. Being able to network and engage in a sheltered space with people who are all interested in proposals, business development, and capture is much better than advertising if those are your potential customers. We recommend that you: Take a step back from selling Focus on demonstrating your capabilities and expertise instead of claiming it Embrace the idea of an audience collective So let's talk about the audience collective because it's a big deal. You may have an audience. We have our existing audience. Both the combined total of everyone else's audience dwarfs both of us. What if we all contribute to the audience? There is some advantage to you in having some of your audience on the site to engage with. It will help you achieve engagement with people you meet. There is also advantage in associating with quality people. We have set PropLIBRARY up so that when you refer people, it can be tracked. And you get rewarded for referring people. Depending on the number of referrals, this could be a little bonus or a major source of revenue. But revenue isn't the point. The point is to recognize participants who contribute to the audience collective. We will be doing this actively and it's probably worth more than the referral revenue share. Since you may be wondering for each person you refer who subscribes for 3 months, you'll get credit for one month. Refer 12 subscribers and a year of subscribing to PropLIBRARY is free of charge. Refer 1200 subscribers and the Make 1,200 referrals at the Premium level and the cash-out value to you would be $38,400. However, getting recognized on our site and in out newsletter for being a top referrer could be worth even more than that if it brings you new clients. There are also opportunities here: To demonstrate your experience through discussions on PropLIBRARY Publish articles and get in front of the audience Publish ebooks, presentations, or other files and charge what you will for them Create online courses and sell them to the audience The advantage of putting your online training here is the audience. You have just as many opportunities to get in front of the audience here as we do. If our approach to building an audience collective is successful, then consultants like you could earn more on PropLIBRARY than we do from hosting it. And because an audience collective creates an audience far larger than our own, if that happens we will be quite happy with the outcome. This post is plenty long enough. Feel free to ask questions, drill down to specifics, or move the discussion in the direction you want it to go.

-

I work for a company. Is PropLIBRARY for me?

PropLIBRARY is about two things: Improving your win rate Networking and engaging with other professionals who have similar interests The majority of our customers are companies that do business with the government (B2G) and companies that do business with other companies (B2B). In both cases, it's mostly companies that win business through competitive proposals or who are interested in best practices for maximizing their business capture rate. Some of our customers are consultants, service providers, or product companies. They also have an interest in improving win rates, whether it's their own or their customers' win rate. On PropLIBRARY, you can network in both groups, find resources, and learn from many different perspectives. We cater to both, focusing on topics like career development and process implementation for people who work at companies and on building an audience collective with consultants. We very carefully manage the value in being able to discover resources and the desire to be able to discuss how to do things without being sold to. There is a place for both and that's how we've organized things. Feel free to ask a follow up, or even a completely different question that this may have inspired.

-

Marketing Materials for Government Contracting

until

Explore marketing materials for your business from your Capability Statement to and other tools including your Business Cards, LinkedIn profile, Website and even the small business Email account. Join us to learn more about all these and more. Presenter Nestor Astorga, Business Development Specialist, SBA, San Antonio District Office Event information and registration -

Micro-Purchase Mastery for Small Businesses

until

For many small businesses, the easiest point of entry into the world of government contracting is through micro-purchases. Micro-purchases are low-value buys that don’t require lengthy bidding or complicated proposals. These purchases, often made with a government credit card, can be your stepping stone to larger opportunities. In this webinar, you will learn how to: Understand federal, state and local micro-purchase thresholds Position your products and services to be “micro-purchase ready” Build relationships with agency buyers and procurement cardholders Stay compliant while growing your pipeline Presenter: Shawn Rogers, Procurement Consultant, Kentucky APEX Accelerator. NOTE: Login instructions will be sent the morning of the event. Event information and registration -

Example of Cross-Reference Matrix Creation

Cross-reference matrix creation sounds complicated in text. View this slide show to see how it works.

-

Introduction to creating a cross-reference matrix

Creating a compliance matrix sounds complicated in text. View this slide show to see how it works.

-

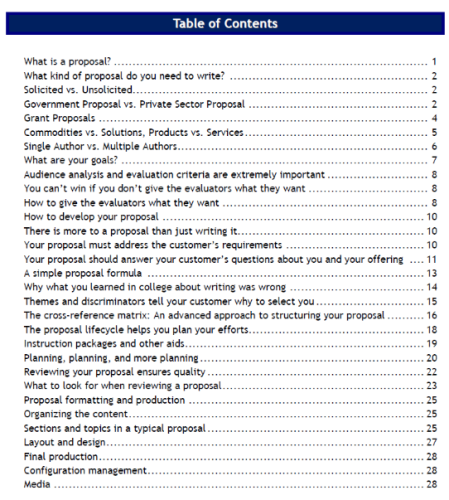

A Better Way to Figure Out What Should Go Into Your Proposal

- 7 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

A manual we published to help people implement Proposal Content PlanningFree -

How to Survive Your First Business Proposal

- 6 downloads

- Version 1.0.0

Before we wrote the MustWin Process Workbook, we published a series of tutorials that included "How to Survive Your First Business Proposal."Free